The vision

Every single one of you has that indomitable spirit. But so many people don’t let it out. They don’t realize the power they have to influence and change the world. And so I’m saying to you, let your indomitable spirit make a difference.

— Jane Goodall, March 30, 2024, at the Moore Theatre in Seattle

The spotlight

Going to see Jane Goodall speak is not unlike going to a sold-out concert of one of your favorite artists. On Saturday, I arrived at the Moore Theatre in downtown Seattle, where the renowned ethologist would be talking about her life and work, to find a queue already wrapping around the block. Eager attendees — mothers and daughters, young couples, and groups of gray-haired friends — took selfies with the theater sign bearing her name. Just days before her 90th birthday (which she celebrates today, April 3), it was clear her place in the cultural landscape has yet to wane.

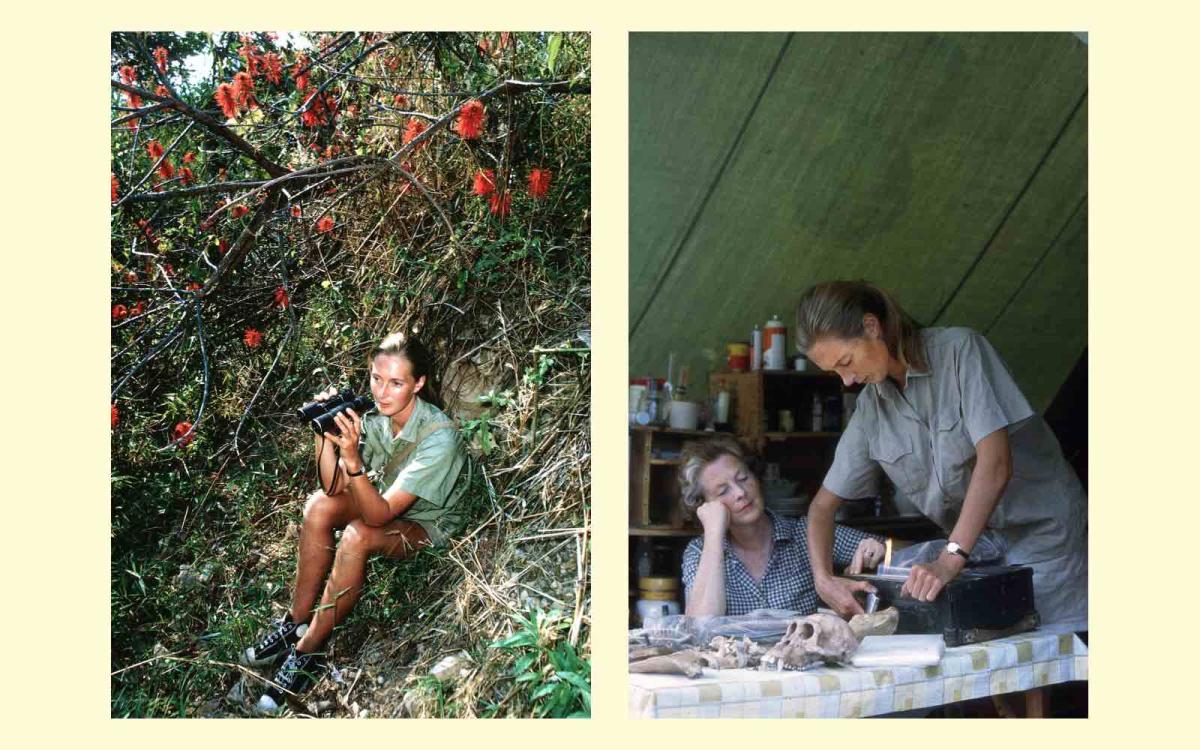

“I’ve always found this interesting about Jane — because she has spanned so many chapters in her life, depending on an individual’s age, they have a different understanding of who she is,” said Anna Rathmann, executive director of the Jane Goodall Institute. Older people may remember her as the young, beautiful blond scientist who was photographed for National Geographic, sitting with her binoculars in the Tanzanian jungle. Others may be more familiar with her work as a public speaker and advocate for conservation. “And then you talk to some of the youth activists and the younger people, they see her as this mother earth elder figure,” Rathmann said. “They see her for the wisdom that she represents. And I think that’s really powerful.”

Even as she reaches her 10th decade, Goodall has no plans to retire. She has said that she’ll keep up her demanding schedule of traveling and public speaking until her body prohibits her from doing so.

“She’ll frequently get asked by journalists, ‘Oh, Jane, you’ve lived this amazing life, you’ve done all these things, you have all these accolades. What’s your next adventure?’” Rathmann said. “And she’ll kind of sit there contemplatively, and then she’ll go, ‘My next great adventure will be death.’”

As Rathmann noted, this answer is in some ways humorous, and a bit disarming. But it’s also, of course, true. It speaks to Goodall’s genuine curiosity about the world and its natural processes — the throughline of a career that started with that curiosity about the natural world and lasted long enough to turn to the desperate need to protect it.

“There’s some connective tissue there about being deliberate and choosing to not live in fear, to not live in despair,” Rathmann said.

![]()

When I made it into the theater, nearly a full hour early, the 1,800-seat auditorium was already bustling. The people who sat behind me remarked on Goodall’s ability to “pack the house.” And just before her talk was scheduled to begin, the crowd launched into a chorus of “Happy Birthday,” followed by a standing ovation when she stepped out to the podium.

“Well, wow. That was an amazing welcome,” Goodall said.

At the start of her talk, she told us that the only way she’s able to deal with such overwhelming public admiration is because there are, as she put it, two Janes. “There’s this one standing here, just a small person walking onto a stage, with feelings like all of you. And then there’s an icon. And it’s the icon that you greeted.”

The sense of adoration for Jane the icon — and the specialness of getting to see her there in person — was almost palpable in the room. If the buzz surrounding the event had some of the atmosphere of a big concert, the talk itself felt like sitting at the feet of your own grandmother, drinking in every word of her stories.

Goodall was dressed mostly in black, with pops of red and and yellow decorating a shawl that almost resembled wings. Her hair was pulled back in its signature ponytail. Once or twice, she shared video clips on the large projector behind her. And near the end of her talk, folk musician Dana Lyons joined her onstage to sing two songs, including a tribute titled “Love Song to Jane.” But apart from that, the talk was simple and intimate. Just Goodall standing at the podium (yes, standing, the entire time) sharing in her slow, deliberate tone, stories about her life — each one building to a lesson about hope, tenacity, and our duty to the future.

Jane Goodall greets the crowd at the Moore Theatre in Seattle. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

“I was born loving animals. And I don’t know where that came from. I was just born with it and my mother supported it,” Goodall began. She recalled how her mother took her on holiday to a farm when she was about 4 years old. For two weeks, her job was to collect the eggs from the hen house. But a young, curious Goodall wanted to understand how an egg could come out of a chicken. And so, apparently, she waited in a hen house for about four hours to witness the act — and not knowing where she was, her mother was getting ready to call the police when Goodall reappeared at the house, covered in straw, ecstatic to share the story of how a hen lays an egg.

“When you look back on that story, wasn’t that the making of a little scientist?” Goodall pondered. “A different kind of mother might have crushed that scientific curiosity. And I might not be standing here talking to you now.”

Unable to afford a college education, Goodall trained as a secretary when she was 18 (“which is very boring,” she said), and then waited tables to save money for what had been her dream since childhood: to travel to Africa and study wild animals.

She finally made it from London to Kenya, on a boat ride all the way down around Cape Town that took nearly a month, she said, to groans from the audience. “It was a magic journey,” Goodall added. In Kenya, she met the famous paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who happened to be in need of a secretary. Leakey ultimately arranged Goodall’s first excursion to study chimpanzees in the wild — something no researcher had done before.

When Jane arrived at what is now Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania (accompanied by her “same amazing mom”), it took several more months of patience and determination for her to even get close to the animals. But when they did eventually lose their fear of her, her discoveries, and her approach, rocked the scientific world.

Photos of Goodall and her mother at Gombe — taken by Dutch photographer and nobleman Hugo Van Lawick, whom Goodall later married. JGI / Hugo van Lawick

Chimps are humans’ closest living relatives, and Goodall found that they resemble us in some ways that were surprising and even controversial at the time. Her initial groundbreaking discovery was that chimpanzees make and use tools — something that was thought to be a uniquely human trait. But she observed other similarities as well. Chimpanzees show affection through hugging and kissing. They have complex social relationships and individual personalities. They can be brutally violent toward one another, and they can also be altruistic.

After her initial breakthrough in 1960, Goodall received funding to extend her research in Gombe, which continues to this day as the longest-running field study of chimpanzees. She first had to obtain a Ph.D. at Cambridge, where she was told she had been going about things all wrong. “You shouldn’t have named the chimps, they should have numbers, that’s scientific. You can’t talk about them having personalities, minds, or emotions. Those are unique to humans. You can’t have empathy with them because scientists must be objective.” Goodall never argued with her professors, but she considered all this to be “rubbish.”

She went back to Gombe, continuing both as a researcher and the subject of film and photographs that contributed to a shift in the way humans, including scientists, thought about animals and the natural world. “They were the best days of my life,” Goodall said. But then something else shifted.

“I just felt so at home in the forest,” she recounted. “So why did I leave? I left because, at a big conference in 1986, I came to understand the extent of the deforestation going on across Africa.” She also learned about the cruel treatment of chimps being kept in captivity for research. “I went to that conference as a scientist, planning to spend the rest of my life in Gombe. But I left as an activist. I knew I had to do something.”

Jane Goodall with a chimpanzee at the Tchimpounga sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. JGI / Fernando Turmo

Goodall became a speaker, using the public’s interest in her life to share messages of action. She wrote and spoke directly to decision-makers, including the former director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins (and, thanks in part to her advocacy, the NIH ended its use of chimpanzees in invasive biomedical research in 2015). Through the Jane Goodall Institute, she has taken a community-centered approach to conservation and habitat restoration. “Right from the beginning, we went in and asked the people what we could do to help,” Goodall said.

Around this point in her talk, Goodall described how she sees humanity “at the start of a very, very long, very, very dark tunnel. And right at the end of that tunnel is a little star shining. And that’s hope.” The tunnel is climate change. It’s also biodiversity loss, poverty, discrimination, and war, she said, and we’ve got to do what it takes to get ourselves to the light at the end.

Goodall’s stories are largely focused on the earlier parts of her life and career — stories she has probably told hundreds of times before, although that doesn’t lessen their impact. She doesn’t offer reflections about her milestone birthday, or spend much time belaboring warnings about how the world has changed over her decades of work. Although our understanding of the most pressing problems facing the world has changed, Goodall’s message largely hasn’t. The climate crisis is another issue to which Goodall applies her message of agency, empathy, and hope.

![]()

“Seeing Jane Goodall filled my cup,” said Darby Graf, a recent college graduate who now works in advocacy and inclusion in higher education. We met on the long journey down the stairs after Goodall’s talk. “There are a lot of things in this life that empty my cup, but hearing her speak filled me with hope. I didn’t know how much I craved that until I started crying partway through her speech.” (This phenomenon is apparently so widespread it is sometimes known as “the Jane effect.”)

I experienced a version of the Jane effect, too — there is something about Jane Goodall, her gentleness and accessibility, that reaches people emotionally. David Attenborough, who is himself a venerated naturalist turned climate activist, called it “an extraordinary, almost saintly naiveté.”

“Jane has an amazing capacity to view everyone as individuals,” Rathmann said. That has been a theme in her work with animals, but it also guides her approach to advocacy today, Rathmann said. “Because an individual can change their mind. An individual can create a ripple effect. And it’s a profound experience to change one individual who then can change a whole host of others.”

Rathmann added that Goodall never sought out global celebrity. But she has accepted the role of icon and given it her all. “She is keenly aware that there is someone in that audience who needs to hear whatever it is that she has said,” Rathmann said, someone who will then take that experience with them.

Still, on Goodall’s 90th birthday, sitting in the glow of Jane the icon, it’s hard not to think about Jane the human and what she herself views as her next great adventure — and whether there is anyone out there who can pick up the torch with quite the same cultural influence with which she has wielded it.

Climate journalist (and former Grist fellow) Siri Chilukuri has been a Goodall fan since the third grade, which played a big role in her decision to enter this field. Today, she said, she thinks about “how to make space for more Jane Goodalls in the world.”

“You know, how does that legacy continue? How do those conversations keep happening? How do those rooms keep filling up?” she said. Chilukuri’s reporting has focused on bringing those new voices to the fore, especially the people most impacted by the climate crisis — many of whom are also at the forefront of solutions. “There’s so many people with so many incredible stories to tell that also have to do with understanding how climate change is a threat to our world,” she said. “And those are people that we should be trying to give platforms as well.”

Goodall, for her part, has said that she respects young activists like Greta Thunberg for their anger and confrontational approach to climate activism. Although it stands in stark contrast to her tone, that anger speaks to the era of the climate crisis we are now in — an era very different from the one in which Goodall began her advocacy.

But the Jane Goodall Institute has plans to continue Goodall’s own legacy and voice as well. “Jane will always serve as that inspiration, as that figurehead of the organization,” Rathmann said of the institute’s work. “In terms of, like, 50 years from now, what is the organization? My hope is that it’s honoring Jane’s own life and legacy, having generations engaged in her work who never knew her personally, who never got the opportunity to come and see her speak in person. Several generations from now, I hope that, if we do it right, they will still be inspired and participating in this.”

“Every single one of us matters, has a role to play, makes a difference every single day,” Goodall told the crowd on Saturday. But the closing note of her talk was not about individual agency. It was about collective action.

“I just want to thank you,” she said to the team at the Jane Goodall Institute, the volunteers who support the organization’s mission, and the entire audience — those of us who simply came out to fill the room. “Because it’s together that we can make this a better world. We’ve got to get together to make a difference, now, before it’s too late.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

More exposure

A parting shot

One of Goodall’s proudest legacies is Roots & Shoots, an initiative of the Jane Goodall Institute that aims to empower young people to be environmental leaders in their communities. The program is active in at least 75 countries — although, Rathmann noted, it’s difficult to get a complete picture of the scope because the program is grassroots in nature. Here, Goodall joins a group of youngsters releasing baby sea turtles in Santa Marta, Colombia.