In between chemotherapy, a double mastectomy and all the other medical appointments that come with a cancer diagnosis, Katie McKnight rushed to start the in vitro fertilization process in hopes that she could one day give birth when she recovered.

McKnight, 34, of Richmond, Calif., was diagnosed in 2020 with a fast-spreading form of breast cancer. IVF can help boost chances of pregnancy for cancer patients concerned about the impacts of the disease and its treatment on fertility. The process involves collecting eggs from ovaries and fertilizing them with sperm in a lab, then implanting them in a uterus.

But after having begun the process — being sedated to retrieve her eggs and paying hundreds of dollars annually to properly store the embryos made with her husband — McKnight can’t afford right now to get the embryos out of a freezer.

Katie McKnight, 34, of Richmond, Calif., takes a photo before her first egg retrieval for IVF after a breast cancer diagnosis in 2020.

(Katie McKnight)

“You either have to be able to access a lot of money, or you just keep them frozen and suspended there. It’s such a weird place to be,” McKnight said earlier this month as she prepared to head into her fifth reconstructive breast surgery. “I got this far, now how am I going to finish this? How am I going to actually realize this dream?”

California — celebrated by women’s advocates as a reproductive health haven — does not require that insurance companies cover IVF.

McKnight, who serves on the board of Bay Area Young Survivors, a support group for young breast cancer patients, is among those lobbying for state legislation to change that. She and her husband hope to implant an embryo as soon as this year, worried that time is of the essence as she is at high risk of a new cancer starting in her ovaries. McKnight has health insurance through her job at an environmental research nonprofit but it does not cover IVF.

On average, IVF costs Californians at least $24,000 out of pocket, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Cost varies depending on treatment — patients typically require multiple rounds of IVF to be successful — and whether employers provide insurance coverage for the procedure. Twenty-seven percent of companies with more than 500 employees offered IVF insurance nationwide, according to a 2021 survey.

Under a bill signed into law by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2019, McKnight was able to have her egg retrievals — a first step in the IVF process — covered by insurance ahead of lifesaving chemotherapy, which can cause infertility. Medical patients who face infertility because of treatment are insured under that law, but that coverage stops short of including fertilization and embryo transfer.

A new bill has been introduced in the state Legislature this year that would require that large insurance companies provide comprehensive coverage for the treatment of infertility, including IVF.

But the bill could be costly and faces an uphill battle as the state grapples with a multibillion-dollar budget deficit. Similar proposals have failed in the past, including an attempt last year that never made it to the governor’s desk, facing opposition by insurance companies that said new mandates would result in higher premiums for all.

IVF is especially important to McKnight because it has allowed her through genetic testing to identify which embryos have the BRCA gene mutation, which is hereditary and significantly increases the chance of breast cancer. She has decided to discard those embryos because of concerns about passing cancer on to her children.

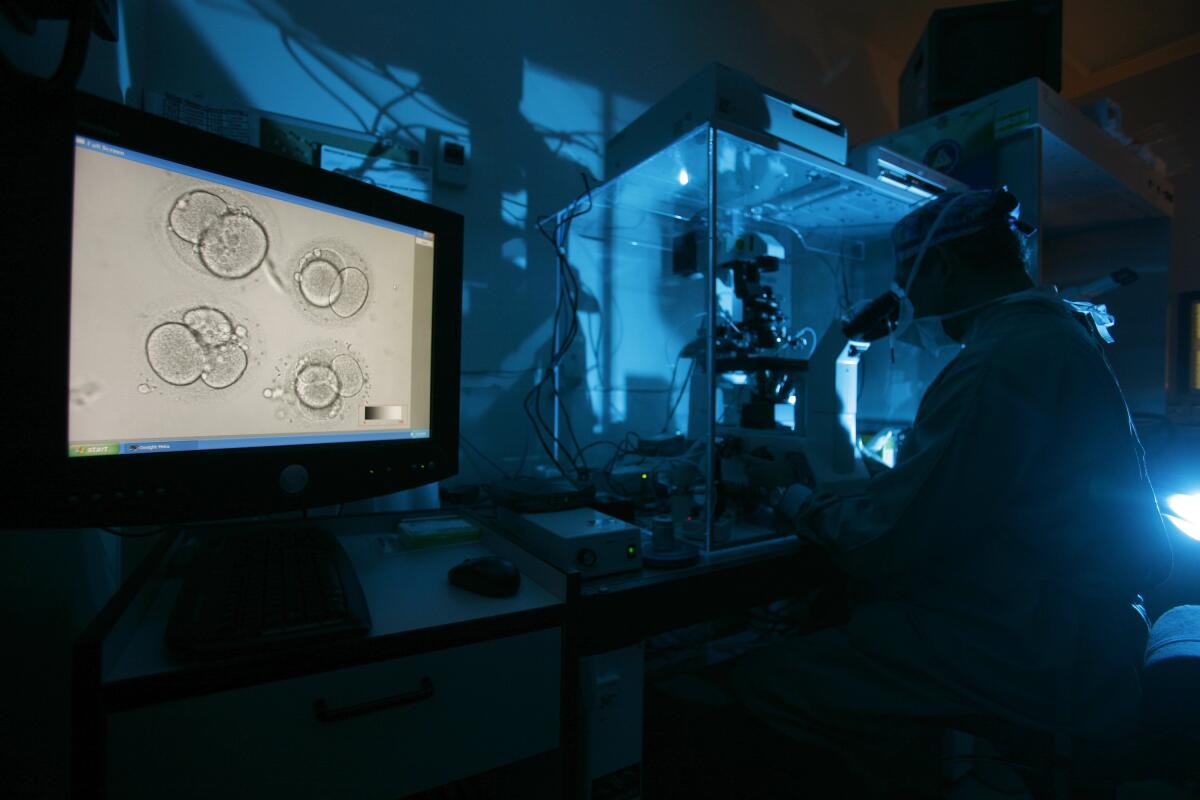

An embryologist works at the Virginia Center for Reproductive Medicine in Reston, Va., in 2019.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

McKnight cried when talking about recent political debates over IVF happening nationwide after an Alabama court ruled in February that frozen embryos can be considered “children” and that those who destroy them can be held liable for wrongful death.

The decision disrupted IVF appointments in Alabama, and state lawmakers there rushed to create legislation aimed to protect the procedure. But uncertainty remains about access amid outstanding legal questions.

More than a dozen states have introduced “fetal personhood” protection laws this year. Those measures could potentially sweep IVF into religious arguments opposing abortion rights and stoking fears about further reproductive health restrictions after the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision rolled back a federal abortion rights guarantee.

“It terrifies me. It’s unfathomable to me,” McKnight said. “I do not want to put a child into this world that has to go through all of the hard stuff that I’ve lived, and I feel like that is my choice.”

Infertility is common. According to the CDC, about 1 in 5 married women of childbearing age are unable to get pregnant after one year of trying.

More than 11,000 babies were born in California in 2021 using assisted reproductive technology such as IVF — nearly 3% of all infants born in the state that year, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

More than a dozen states, including New York, Arkansas and Connecticut, mandate that health plans provide some coverage for IVF.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine said that California — home to the most progressive abortion laws in the country — is failing to fulfill its role as a “reproductive freedom” state.

“California still has significant work to do to ensure that all people can make personal decisions about their reproductive lives and futures. True reproductive freedom means that all people can decide if and when to start or grow a family,” the group said in a statement in support of SB 729.

In addition to extending insurance coverage to IVF, SB 729, introduced by state Sen. Caroline Menjivar (D-Panorama City), would also redefine “infertility” in health plans, extending services to LGBTQ+ couples who don’t meet current standards to secure fertility services.

Most health plans that do offer IVF coverage measure infertility based on whether a man and woman fail to get pregnant after a year of unprotected sex, excluding from coverage LGBTQ+ couples seeking to use fertility services to start a family.

The new bill would broaden the definition of infertility to include “a person’s inability to reproduce either as an individual or with their partner without medical intervention.”

The issue is personal for Menjivar. She and her wife recently chose to delay plans to start a family through fertility services such as IVF and instead buy a home, after weighing the costs. She said she has friends who have traveled to Mexico for cheaper fertility care.

“When we talk about Alabama … we have barriers like that in California. The physical barriers exist in California, where people cannot afford this,” Menjivar said.

California Sen. Caroline Menjivar (D-Panorama City), left, and former Senate leader Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) at the state Capitol.

(Fred Greaves / For CalMatters)

The bill has been opposed by the California Assn. of Health Plans and a number of insurance companies that warn that such single-issue mandates lead to increased premiums for business owners and enrollees.

According to a legislative analysis of the potential costs conducted last year, the California Health Benefit Review Program estimated employers and enrollees would spend a total of an additional $183 million in the first year of the bill’s implementation, and nearly double that the following year. California could face potentially tens of millions more in separate costs, according to that analysis, due to increases in premiums for state employees.

“While this bill is well-intentioned, it will unintentionally exacerbate health care affordability issues,” the California Chamber of Commerce, which also opposed the bill, said in a statement.

The latest cost estimate reflects Democrats’ attempts to narrow the bill and drive the price down, exempting small health plans, religious employers and Medi-Cal — which provides insurance to low-income Californians — from the proposed mandate to cover IVF.

New IVF policy debates have posed a political quagmire for some Republicans who have used “personhood” arguments to oppose abortion but do not want to see IVF access encroached.

California Assembly Republicans — some of whom are opposed to increasing abortion access — introduced a resolution last month calling on the state to declare that it “recognizes and protects” access to IVF for women “struggling with fertility issues” and encouraged the same at the federal level. The resolution also calls on Alabama to overturn its ruling.

“IVF has helped so many families actually have children so we need to make sure we’re protecting access to it,” said Assemblymember Josh Hoover (R-Folsom), who co-authored Assembly Concurrent Resolution 154. “We can’t go backward on IVF.”

But several state Republicans who support that resolution opposed last year’s attempt to insure IVF in California.

The insurance bill did not make it to the Assembly last year, and Hoover said he is unsure of how he will vote if it makes it to his house this year, voicing skepticism about the costs to small-business owners and taxpayers.

For Democrats like Menjivar, the Republican-led resolution — which specifies that IVF is for women struggling with fertility issues and does not mention LGBTQ+ families — is viewed as a farce.

“It’s all talk,” she said. “This does absolutely nothing, there’s no meat to it whatsoever.”

Menjivar said that she will not support that resolution without changes. She is angry about “hypocrisy” she’s seen from Republicans nationwide who she believes voted for antiabortion policies that have led to the IVF problems arising now.

“They made their bed and they’re trying to squirm out of it and they’re getting stuck,” she said.

Source: www.latimes.com