Washington — In December 2022, Paul Whelan was sitting in a factory at a Russian labor camp in Mordovia, more than seven hours east of Moscow, adding buttons and buttonholes to winter coats.

He was summoned to the prison warden’s office and was hopeful that someone from the U.S. government was calling to tell him they had finally secured his freedom, Whelan told “Face the Nation” in his first interview since he was released in a complex prisoner swap in August. Instead, a U.S. official told him, it was women’s basketball star Brittney Griner who was going home. Russia had agreed to release her in exchange for Viktor Bout, a convicted arms dealer nicknamed the “Merchant of Death.”

“I asked him point blank, I said, so what else do you have to trade? And he said, ‘Nothing,'” Whelan recalled of the phone conversation. “How do you now get me back? And he said, ‘Well, we’re going to reconvene tomorrow to discuss that.'”

“You realize what you’ve done here,” Whelan said he told the official. “You have no one to trade. They don’t want anyone else. And he said, ‘Yes, yes, we realize.'”

CBS News

The Marine veteran was two years into his 16-year prison sentence after Russia arrested him in 2018 on what the U.S. found to be fabricated espionage charges. By then, Washington and Moscow had swapped Trevor Reed, a Marine veteran who had been detained in Russia since 2019, for Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian pilot convicted in the U.S. of drug smuggling. Russia had detained Griner in February 2022.

Whelan, who the U.S. State Department determined to be wrongfully detained, had expected to be freed with Reed, whose health was in decline. He said he learned of his exclusion from that trade over the radio while he was working in the factory.

“All I could do is just sit back and try to process what I just heard in Russian,” he said. “All I could do was just keep on working.”

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

Whelan was visiting Moscow for a friend’s wedding in December 2018 when he was arrested. In footage of his arrest released by Russian state media, Whelan is in his hotel room bathroom talking to an acquaintance who hands him a flash drive moments before agents from Russia’s intelligence agency, the FSB, detained him. Whelan declined to say more about the acquaintance, but he believes he was targeted.

“I hadn’t done anything. I hadn’t committed espionage,” he said.

At the time, Whelan, who has citizenship in the U.S., Canada, Ireland and the United Kingdom, was the global head of security for auto parts supplier BorgWarner. The company laid him off about a year into his detention.

“If you can call an act by an employer un-American, that was un-American,” he said. “What really bothered me, wasn’t too much losing my job, but that BorgWarner continued to do business in Russia while I was being held prisoner there. They refused to cooperate with the U.S. government. They refused to cooperate with people that were trying to help me. … They haven’t done anything to support me or my family.”

CBS News reached out to BorgWarner for comment on Whelan’s remarks. The company referred to its August statement when Whelan was freed, in which it claimed his December 2018 trip to Russia was personal, not business-related. Whelan told CBS News that the company had paid for his visa to enter the country, and that he had been sending work emails and handling work-related phone calls on the day he was arrested.

Whelan said soon after his arrest, FSB agents told him not to do “anything rash” and he “shouldn’t worry” because this was all part of Russia’s ploy to get Yaroshenko, Bout and Maria Butina, a Russian agent who had sought to infiltrate conservative American political circles.

After Butina’s deportation from the U.S. in 2019 following her prison sentence and the two prisoner exchanges in 2022, Russia had secured the release of all three.

Meanwhile, Whelan’s family had grown increasingly worried about his well-being.

“How do you continue to survive, day after day, when you know that your government has failed twice to free you from a foreign prison? I can’t imagine he retains any hope that a government will negotiate his freedom at this point,” his twin brother, David Whelan, wrote in an email to reporters on Dec. 8, 2022.

Patrick Semansky / AP

As negotiations for his release stalled over the years, Whelan said “it did play with my mind.”

The first two years of Whelan’s detainment he was kept at Moscow’s notorious Lefortovo Prison, where the lights were kept on 24 hours a day in his cell. At the labor camp, guards woke him up every two hours every night for four years.

“Getting off that sleep pattern has been very, very difficult,” he said. “It is still tremendously difficult to sleep for six or eight hours at a time.”

The labor camp housed mainly prisoners from Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, he said, describing his fellow prisoners as a “close-knit family.” They were much younger than Whelan, now 54, and helped him figure out how to send messages back and forth through the prison communication network with Reed before his release, he said.

“Knowing that he was there … gave me some strength and helped me get through my ordeal,” Whelan said. “I think him knowing that I was close by and doing the same helped him, too.”

They also had secret cellphones, Whelan said, that enabled prisoners to communicate with those from their camp who had been sent to the frontlines in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“They would communicate with us, and the communication from them, I was passing back to the four governments through illegal cellphones,” he said, explaining that the prison guards turned a blind eye. “A Russian prison guard gets $300, $400 a month. You give them a carton of cigarettes, and you can do just about anything you want.”

When Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was arrested on trumped-up espionage charges in March 2023, Whelan and his family again worried that he would be left behind. His family consistently pressed the Biden administration to do more to secure his release. Whelan also advocated for his own freedom, calling journalists and, in separate phone calls, expressing his frustrations directly to Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs Roger Carstens.

Carstens said his conversation with Whelan after Griner’s release was “one of the toughest phone calls” he has ever had.

Alex Brandon / AP

It took months of painstaking negotiations through diplomatic and intelligence channels for the final deal that would grant freedom to both Whelan and Gershkovich to come together. The deal hinged on President Biden persuading German Chancellor Olaf Scholz to release convicted FSB assassin Vadim Krasikov.

On Aug. 1, in one of the largest prisoner swaps since the end of the Cold War, Russia released 16 prisoners, including political prisoners aligned with deceased opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and Western countries released eight Russians, including Krasikov. Russian-American radio journalist Alsu Kurmasheva and Vladimir Kara-Murza, a U.S. green card holder and Kremlin critic, went free alongside Whelan and Gershkovich.

During Mr. Biden’s visit to Berlin on Friday, he thanked the German chancellor for his help in securing the release of the wrongfully detained Americans, according to the White House’s summary of their meeting.

Whelan said he was held in solitary confinement in the five days before his release.

He didn’t believe he was on his way home, until the small CIA plane carrying him and the other freed detainees flew over the English Channel. “I wasn’t expecting to see the White Cliffs of Dover, but I did,” Whelan said, tearing up for the first time in the interview.

“You know, during the war, they guided the Spitfire pilots back,” he said, referring to how the cliffs were a prominent marker on the return flight path for British fighter planes during World War II. “For me, it was guiding me and Evan and Alsu back to the United States.”

Alex Brandon / AP

He didn’t know that Mr. Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris would be waiting for him on the tarmac when they landed shortly before midnight at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland. Wearing unwashed clothes that he had brought to Russia in 2018 that were now too big for him, Whelan was the first to disembark from the plane that had traveled from Ankara, Turkey, where the exchange occurred.

“I was told I could go first because I’d been held the longest,” he said. “You see the stairs come down, and the president and vice president are looking up at the plane. I’m in the plane looking out, I’m looking at all the media, saying, ‘Wow, OK, I need to figure out how to do this really quickly.'”

He walked down the eight steps and saluted Mr. Biden. He spoke briefly with the president and vice president before walking over to his sister, Elizabeth Whelan, who had traveled to Washington more than 20 times to push the government to take action. Mr. Biden later took the American flag pin off the lapel of his suit jacket and pinned it on Whelan’s shirt.

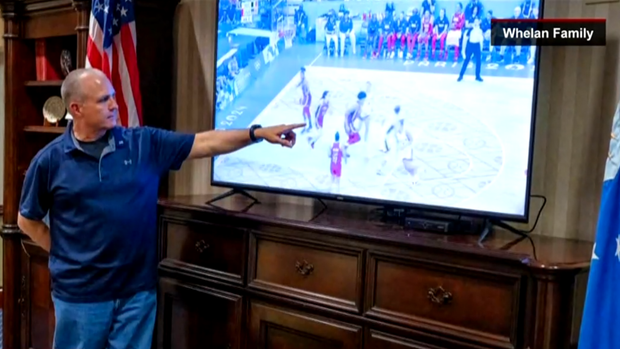

While Whelan was waiting to head to San Antonio, Texas, for medical evaluation, the Paris Olympics played on the television in the distinguished visitors lounge at Joint Base Andrews.

“And as I’m looking, I said, ‘Hey, look, it’s Brittney. Brittney’s on TV,'” Whelan said.

Griner, who won her third consecutive Olympic gold medal in Paris, had advocated for Whelan’s freedom after her release.

“It was one of those incredible moments,” he said.

Courtesy of the Whelan family

www.cbsnews.com