It all started with a “Tantrum.”

That’s the name given to the Pro Touring-style 1970 Dodge Charger, a restomod completed by a small shop in Grafton, Wisconsin, in 2015. With a low stance, carbon-fiber body panels, a massive 1,350-hp marine engine, and a beautiful finish, the Tantrum caught the eye of the producers of the “Fast & Furious” franchise when it appeared at the 2015 SEMA show, earning it a role in the seventh installment of the series, “Furious 7.” From there, that Tantrum made the builder, SpeedKore Performance Group, one of the highest-end, most elite restomod shops in the country, especially for Mopar fans.

Speedkore 1970 Dodge Charger Tantrum

“The Charger is an iconic body style,” Tom Porter, senior business development manager for the shop, told Motor Authority. “No one really had done anything as wild (as Tantrum), so if you’re going to get into the Pro Touring space you gotta come in and you gotta do something different.”

SpeedKore started as a passion project for Jim Kacmarcik, Chairman and CEO of Kacmarcik Enterprises. It’s part of the Kacmarcik Group of 15 companies in southeastern Wisconsin that includes Kapco Metal Stamping, an industrial coatings business; the House of Harley-Davidson; a trucking company; a music publishing company; and multiple philanthropic nonprofits.

Kacmarcik had worked with another shop to build a personal car and enjoyed the process. He had the resources and the space to start his own company, and having learned about the players in the automotive world in the area, he started to hire them. They included a master fabricator who built drag cars for decades, a master technician with his own small shop, an engineer, and a body man.

The current group consists of just 11 employees, including eight in the shop, two business development managers, and Lyle Brummer, an engineer who figures out how each car will come together. The mix includes older experienced guys, several of whom were there at the start, and younger guys, most of whom trained at WyoTech in Laramie, Wyoming. The shop’s growing reputation has drawn talent to the company, making it easy to hire the pick of the litter.

1970 Dodge Charger Tantrum by SpeedKore Performance

1970 Speedkore Dodge Charger Evolution

SpeedKore

The Tantrum Dodge Charger (top left) burst onto the scene in 2015 and earned a role in

SpeedKore: The projects

After Tantrum, SpeedKore built a BMW, then a Boss Mustang, some late-model Dodge Demons, and some late-model Mustang Shelby GT350s, creating carbon-fiber body panels for each. The cars quickly drew celebrity clients, including actors Robert Downey, Jr. and Chris Evans, comedian Kevin Hart, and Stellantis design chief Ralph Gilles.

One early project made unfortunate headlines. “Menace,” a 1970 Dodge Challenger built for Hart, wasn’t a ground-up build, but the car featured several carbon-fiber components, including a unique take on the original twin-scoop hood. It was powered by a supercharged version of the Dodge 6.4-liter V-8 making 720 hp. In 2019, with a friend at the wheel, Hart was injured in an accident that put him in the hospital for two weeks.

While the company has completed 40-50 builds with varying levels of work, the main attractions are the six ground-up builds SpeedKore has created, all of them Chargers. The cars made news but for a better reason. They were simply beautiful restomods that caught the attention of show judges. The cars won major awards from Goodguys, the SEMA show, and the Car Craft Summer Nationals, and that earned them several stories in the automotive media.

“Our DNA in the brand was developed in the Mopar space,” Porter said. “The Tantrum was really the car. We invested a lot in terms of a manufacturing business in the tooling for the carbon fiber for that type of car, for the ’68 through ’70 B-body cars.”

Those B-body cars include the Dodge Charger and Coronet and Plymouth Satellite, GTX, and Road Runner, among other less exciting cars, but SpeedKore really specializes in the Charger.

After Menace came a second 1970 Charger called “Evolution.” The idea this time around was to go with a full carbon-fiber body on a ground-up project. It sports the Demon’s supercharged 6.2-liter V-8 that sends its 840 hp through a 6-speed manual transmission.

The “Fast and Furious” franchise came calling again, commissioning a car for 2021’s “F9: The Fast Saga.” Called “Hellacious,” the car is a mid-engine 1968 Charger, and it remains the most radical car the shop ever built. It has a wide-body design, a large glass rear window that shows off the mid-mounted supercharged 6.2-liter Hellcat V-8, and a sparse interior with low-back bucket seats. SpeedKore designed the chassis, incorporating a Detroit Speed double A-arm front suspension with a rear cradle from Race Car Replicas. The engine sends its power to the rear wheels through a Graziano transaxle from a Lamborghini Gallardo.

Hart did business with the shop once again, commissioning a 1970 Charger called “Hellraiser.” It boasts a Mopar Hellephant supercharged 7.0-liter V-8 spitting out 1,000 hp and 950 lb-ft of torque.

Gilles, the chief design officer at Stellantis, worked with SpeedKore to build a 1968 Charger of his own. Called “Hellacious,” it also sports Hellephant power.

The most recent ground-up project is a 1970 Charger called “Ghost.” The only full carbon-fiber-bodied car to wear a full paint job, the car takes its name from the white finish. It teams a Hellcat V-8 with a 6-speed manual transmission.

SpeedKore Hellucination 1968 Dodge Charger

SpeedKore Ghost 1970 Dodge Charger

More recent builds include the (counterclockwise from top) Hellucination, Ghost, and Hellraiser Dodge Chargers.

SpeedKore: Pro Touring aesthetic

SpeedKore builds have a clean Pro Touring look. The company’s custom frame pushes them low to the ground. The bodies are mostly stock, but with the drip rails often shaved. They’re tubbed and sit on wide and wider tires wrapping HRE 19- and 20-inch wheels with a modern look. Most show off their dark carbon-fiber body work under a clear coat, but customers are free to paint them any color they want. They look stock but sinister, like the way a performance version of a vintage Charger would look if it were built today to handle a road course.

“We don’t want big blowers sticking out of the hood and things like that. That’s not us, that’s not our brand,” said Porter. “If you’re coming to us, you’re looking for a very, very tight, original looking car.”

“Every car can have its own personality around what the buyer wants,” Porter noted. “For example, ‘I want an AAR hood, etc.’ As long as we don’t bastardize it. The forefathers in 1968, ’69, and ’70, they knew. Those cars, they’re iconic.”

The look caught the eye of Gilles at an LX Springfest several years ago. Gilles told Motor Authority he was attracted to how understated the car was.

“From a distance, it looked like a very nicely done, lowered, kind of a restomod theme but very clean. And the closer I got to it, it revealed the carbon fiber, and the details, and I looked inside and I just couldn’t get over how well made it was,” Gilles said.

The shop will create a rendering for a customer and has worked with designers, including Sean Smith (who designed Tantrum when he worked at the shop), Rami Curry, and Gilles. Gilles designed the hood scoop of his 1968 Charger to fit the Hellephant V-8 in the engine bay, and he also designed the wheels on his car as a modern take on the Hurricane wheels of the General Lee 1968 Charger from “The Dukes of Hazzard.”

SpeedKore Hellraiser 1970 Dodge Charger

1970 Speedkore Dodge Charger Evolution

The retro-modern interiors of the (counterclockwise from top) Hellraiser, Evolution, and Hellucination Dodge Chargers.

The interiors aren’t as stock, but they have a clean, purposeful, and high-quality aesthetic of their own. SpeedKore designs the look in-house and works with the folks at the California shop Gabe’s Street Rod Custom Interiors, Auto Alliance in Appleton, Wisconsin, and the upholstery company Katzkin for upholstery. The dashboards are modern takes on the originals, often done in carbon fiber, and the center consoles are wide and tall to fit the drivelines in the lowered bodies. Modern bucket seats with or without full racing harnesses usually replace the flat seats of yore. The company has its own branded retro-modern gauges made by Classic Instruments, switchgear is often made from billet aluminum, and most builds include a Kicker audio system.

After driving his car, Gilles appreciates another aspect of SpeedKore’s design. “The coolest thing they do that they don’t get credit for is they (flush)mount the windshield like a modern car. So they get rid of the big seals.” Gilles noted that this little detail really updates the look and also makes the car quiet from behind the wheel.

SpeedKore shop tour

SpeedKore shop tour

A 1970 Plymouth Barracuda on the rotisserie for paint prep and installation of heat shield in the tunnel and sound deadener in the floor. That carbon-fiber floor is also shown, as is a carbon-fiber hood.

SpeedKore: Hand-built street machines

While every full SpeedKore build has a VIN, almost nothing from an original muscle car makes it to the final product. That means the donor car doesn’t have to be in good shape. It just needs some of the original’s basic geometry. It’s amazing to look at how a SpeedKore car starts and how it ends up. The shop uses Mopars5150 to source its cars. That company scours the web for Mopars, and has 300-400 cars with clean VINs, Porter noted. “We buy their worst of the worst,” he quipped.

A 1970 Roadrunner, 1970 Charger, two Plymouth ‘Cudas and a Pontiac Firebird in the back lot at SpeedKore awaiting their restomod fates.

SpeedKore disassembles a donor car, acid dips the body, and cuts away everything but the firewall, A-pillars, roof, rear pillars, package tray, and the inside of each rear fender panel in front of the rear wheels. The roof and rear pillars are also just inner structures that will be replaced, usually with carbon fiber. The original frame is cut out, an X-truss is welded in the shell, and the car is put on a SpeedKore frame. Porter estimates that just 5% of the original car remains.

SpeedkorThis is all that’s left of a 1969 Dodge Charger donor car once SpeedKore has stripped away everything it doesn’t need.e shop tour

This is all that’s left of a 1969 Dodge Charger donor car once SpeedKore has stripped away everything it doesn’t need.

This is all that’s left of a 1969 Dodge Charger donor car once SpeedKore has stripped away everything it doesn’t need.

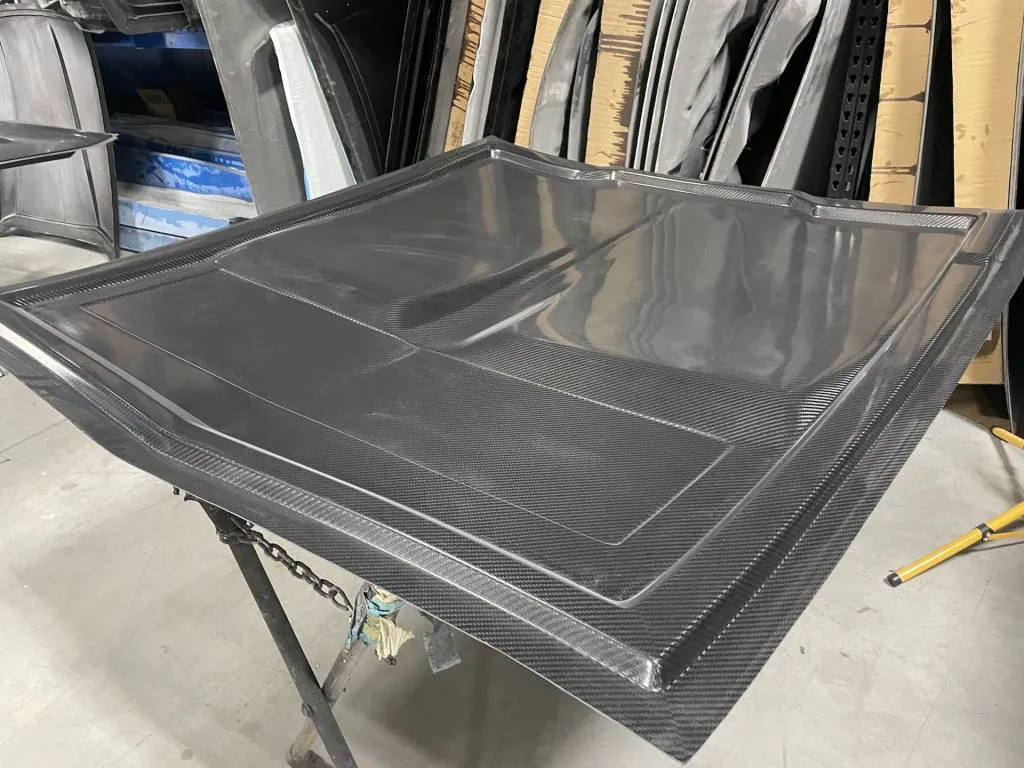

SpeedKore makes carbon-fiber body panels for the 1968-70 B-body Mopars for use on project cars, selling them through its online store. It also offers bumpers, splitters, and other components for vintage and late-model Dodge, Plymouth, Ford, and Chevrolet models. Its carbon-fiber Dodge Challenger components are available through Direction Connection. The company also makes Harley-Davidson fenders, headlight bezels, side covers, and other trim parts, and sells them online and through Harley dealers.

The final build quality of the Charger body panels is better than anything that came from the factory. That’s not saying much because Mopars in the muscle car era were known for poor fit and finish.

To make its body panels, SpeedKore first scans three versions of a B-body car and averages the results in CAD, making adjustments for the best fit part-to-part. Smaller parts can be 3D scanned or created in CAD.

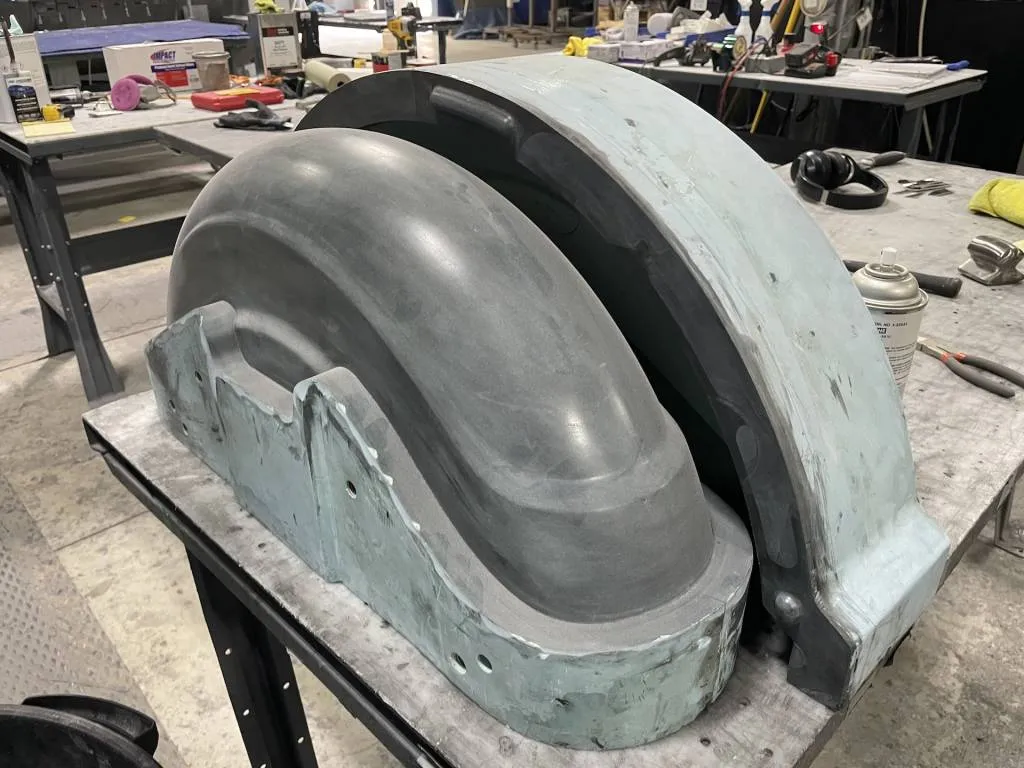

The CAD data is then used to make a plug that will serve the master form of the final part. Made from a composite material and CNC machined to shape, the plug is produced by a vendor. When it comes back, it’s sealed, prepped, and cured. It’s now ready to act as the master part shape from which pre-impregnated carbon-fiber molds are made.

The mold is the negative of the part and it’s created off of the plug from layers of pre-preg. One mold can make about 20 parts. The process is illustrated below with the master, plug, mold, and final product of a Harley-Davidson fender. The shop’s warehouse is full of molds, and with each one the team learns how to make better and better parts, Porter said.

Carbon-fiber parts are created by first creating a master or plug (first photo), then making a mold off of it (second photo), laying in the carbon fiber, then trimming it. These fenders are for a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

Carbon-fiber parts are created by first creating a master or plug (first photo), then making a mold off of it (second photo), laying in the carbon fiber, then trimming it. These fenders are for a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

Carbon-fiber parts are created by first creating a master or plug (top), then making a mold off of it (bottom left), laying in the carbon fiber, then trimming it. These fenders (bottom right) are for a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

Pre-preg comes in rolls and consists of the carbon-fiber weave impregnated with a resin that helps the final part take its shape. The rolls are stored in freezers until they’re ready to be used.

When it’s time to make a part, a fender for instance, digital information is used to flatten the fender geometry, and a template is created to cut the material to size. A typical fender will consist of one piece in five layers fit into the mold. Thinner material is used for the first two cosmetic layers, and they are backed by three layers of material that are each about four times as thick.

The carbon-fiber layers are laid into a mold and pushed into the cracks, crevices, and angles by hand. The part is then bagged and connected to a vacuum to suck the carbon-fiber more precisely into the mold, a process called debulking.

SpeedKore’s autoclave can hold parts up to 13.5 feet long.

The bag is then put into an autoclave, which is essentially a big oven that also introduces pressure. The vacuum is then reattached, temperature sensors are attached, and the autoclave cycle is run. A typical cycle will last three hours at about 200 degrees. When the cycle is done, the part and mold are pulled out together, debagged, and the mold is split, typically with air, to remove the part from the mold. The piece is then evaluated and any sharp edges are trimmed. Using prepreg for both the part and the mold means they react the same to the temperatures of the autoclave. Porter says the company’s autoclave can hold a part up to 13.5 feet long.

Weave orientation on the cosmetic layers is important. SpeedKore makes sure the weave orientation from the left front fender to the hood to the front bumper to the right front fender to the doors all matches up perfectly. This is done digitally, and the roll of pre-preg is rotated to get the right cut.

SpeedKore tries to be true to the original, so body brackets will fit the same way in the same spots, though they may also be made from carbon fiber.

The complete body is assembled on the car, and may or may not be painted. Most buyers want to show off their carbon fiber either under a clear coat or a darkened clear coat. The shop has its own paint booth to create a glass-smooth finish.

SpeedKore makes its 1968-’70 Dodge B-body frame from 12-gauge steel and assembles it on a frame jig.

SpeedKore shop tour

SpeedKore makes its 1968-’70 Dodge B-body frame from 12-gauge steel and assembles it on a frame jig.

The body fits on a custom B-body frame designed by SpeedKore. It gives the cars a low stance and leaves room for tubbed rear wheels. The frame’s 12-gauge steel is laser cut by Kapco across the street, and each piece has tabs for fitment. Boxed and welded, the frames are assembled on a jig and designed so the fuel and oil lines fit inside their tubing. So far, SpeedKore only has a B-body frame, but the company is working on an E-body frame for 1970-74 Dodge Challengers and Plymouth Cudas.

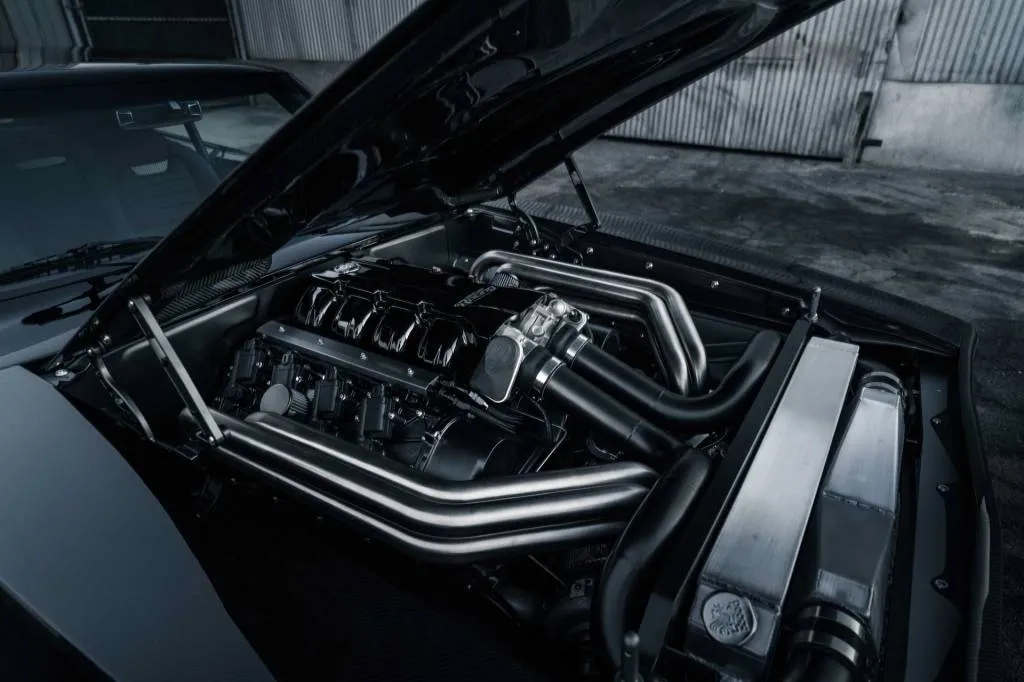

Engines are chosen by each individual buyer, and SpeedKore usually works with Mopar crate engines that are essentially plug-and-play with no need for tuning. The shop has used Demon, Hellcat, and 392 engines, and Hellephant engines. “Our customer can drive our car into a dealership and they can run diagnostics on it,” Porter said.

Tantrum’s Mercury marine twin-turbocharged 9.0-liter V-8 makes 1,350 hp on pump gas.

The engine in Tantrum was unique, though. It was a QCV4 Mercury Racing marine engine. A twin-turbocharged 9.0-liter V-8, it put out 1,350 hp on pump gas or 1,650 hp on 110-octane gas. That power is fed to the rear wheels through a Tremec 6-speed manual transmission and a Ford 9-inch rear end.

SpeedKore knows the engines will fit and the cars will go together well due to technology and pre-planning. “We digitally build the cars to a high degree before we assemble them,” Porter said. The team 3D bluelight scans the engine, the engine bay, and the engine pickup points to preplan how everything will go together. The final result makes for a tidy engine bay that’s jewelry in itself.

In addition to the frame, SpeedKore has its own 4-link rear suspension. The shop usually works with Detroit Speed for the front suspension, and brakes can come from Brembo, Willwood, Baer, or any other source of the customer’s choice. A 14-point roll cage is usually integrated for rigidity and safety.

In addition to the 3D scanner, the shop has a full array of tools to accomplish any task, including mills, lathes, 3D printers, and an English wheel. The shop also has its own paint booth and grinding booth. About half of the 3D-printed parts are made in-house and the other half are sent out to vendors. Billet parts can be designed in-house and sent to vendors as well. For milling and machining projects, the shop will design the part, such as a metal grille, and may even program the tooling path, but it will send out the data to cut the part, often to Kapco.

SpeedKore works on about four cars per year, and the shop might finish one or two. The cars can take up to three years to build and each has 5,000 or more hours of work in it.

SpeedKore Hellucination 1968 Dodge Charger

SpeedKore Hellucination 1968 Dodge Charger

SpeedKore Hellucination 1968 Dodge Charger

SpeedKore: Show and go

With their V-8 power, SpeedKore cars are obviously fast. However, they’re built to turn corners as well.

“The cars are low, they have a great turning radius, full clearance lock to lock,” Porter said. “The cars handle great. You can drive them across the country. You can track ’em. We want people to have a performance vehicle experience.”

Gilles took SpeedKore up on that promise, taking delivery of Hellucination at GingerMan Raceway in Western Michigan. He ordered the car with two sets of wheels and tires, including a set of slicks and a set of Michelin Pilot Sport Cup tires, and put it through its paces with temperatures in the 90s. Porter says Gilles did six to eight laps as a shakedown and SpeedKore adjusted the car’s tune for the track.

“We don’t use the term race car, but they are like a Trans Am race car. That car geared right is capable of 200 mph,” Porter said.

Gilles’ reaction to the car on the track?

“I was pleasantly surprised at how the car handled. It doesn’t handle like a ’68 at all. It handles much more like a modern car. A lot of grip, a lot of braking power. Tons of torque. I mean you barely touch the pedal and the thing is launching you,” he said.

“The car felt very light and agile. The car is well under 4,000 pounds, so it’s quite fun to drive. I was beaming the whole time.”

Hallucination doesn’t have traction control or stability control, but that wasn’t a concern for Gilles. “You respect the car. Nothing scares me, but the car scares me not because it’s tricky to drive but because I have so much into it, you know passion, my heart and soul, time—it took three years to build the car.”

Gilles said he put 6,550 miles on his car in just one year. He also said that the fit and finish is excellent. “It’s as beautifully designed underneath as it is on top.”

Gilles noted, however, that the cars are made for Cars and Coffee events, so they’re not quite finished for regular use. “They don’t use a lot of LocTite, they use anti-seize on most of all their bolts. So I had to. I took the car kind of half apart and I put LocTite on everything because I wanted it to stay cinched on and torqued while I drive it as much as I do. So, I had to kind of, let’s say, road prep it,” he explained.

While Gilles doesn’t even know how much he spent for his car as he paid in several installments as work progressed, this kind of care and effort doesn’t come cheap.

If you have to ask, it’s too expensive. Figure seven figures. Don’t have a tantrum if that’s out of your budget. Given the beauty and capability of the cars, plus the thousands of hours of hand-built expertise, that seems worth the cost.