U.S. prosecutors said Wednesday that they’re discussing a potential plea deal with Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, the long-elusive Mexican drug lord who was arrested last summer and whose son could testify against him if he goes to trial.

Assistant U.S. attorney Francisco Navarro said the plea discussions with Zambada, a leader of Mexico’s powerful Sinaloa cartel, haven’t borne fruit so far, but prosecutors want to keep trying. A judge scheduled an April 22 hearing for an update.

Zambada’s lead attorney, Frank Perez, declined to comment on the discussions.

It’s common for prosecutors and defense lawyers to explore whether they can reach a deal, and the talks don’t necessarily go anywhere.

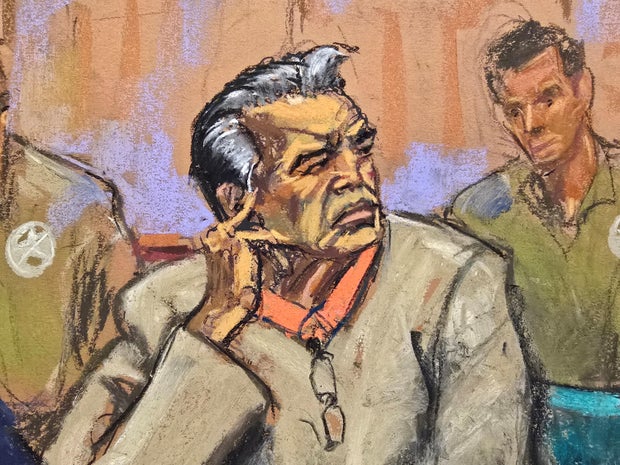

Zambada was an attentive and active participant during Wednesday’s hearing, which focused on whether he wanted Perez to continue representing him even while also representing a potential government witness in the case – Zambada’s son Vicente Zambada.

“I don’t want a different attorney,” the father said through a court interpreter. “I want him, even though this could be a conflict if he represents me and my son.”

Jane Rosenberg / REUTERS

The younger Zambada was charged himself and made a plea deal in the long-running and sprawling U.S. prosecutions of Sinaloa cartel figures. He testified for the government at the trial of the cartel’s infamous and now imprisoned co-founder, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Working alongside Guzmán, Ismael Zambada kept a lower profile and was seen as concentrating more on the business of smuggling than the extremes of brutality, serving as a strategist and dealmaker who engaged with day-to-day operations, authorities say.

At Guzmán’s trial, Vicente Zambada recounted how his father and Guzmán ran the cartel together. At one point, he described corrupt Mexican politicians asking whether the syndicate could help them ship 100 tons of cocaine in an oil tanker.

“They wanted to know if my dad and Chapo could provide that amount of coke,” he told a jury in the same Brooklyn federal courthouse where his father is being prosecuted. At another point, Vicente Zambada recalled hearing a rival drug gang leader say he wanted to kill Ismael Zambada and Guzmán to avenge a botched hit.

Prosecutors said in a court document last month that the son might be called to testify against his father, which could pose a conflict of interest for Perez. For instance, he’d be hindered in cross-examining the son because of the loyalty he owes both clients.

Defense lawyers do sometimes have potential conflicts of interest regarding a client, and federal courts have outlined the steps judges should take to address such situations. Among them is having an independent lawyer advise defendants as they consider what to do about the possible conflict. Zambada had one at Wednesday’s hearing.

Zambada said he realized there could be problems with Perez representing him and his son – “for example, that he will have to hide information that he obtained from Vicente from me.”

U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan ultimately agreed that Perez could stay on the case, noting that Ismael Zambada also has other lawyers who could handle any piece of it relating to his son.

Law enforcement sought the elder Zambada for years before his startling arrest in July at an airport near El Paso, Texas, after arriving in a private plane with one of Guzmán’s sons, Joaquín Guzmán López. He, too, was wanted by U.S. authorities.

Zambada has said he was kidnapped in Mexico and hauled to the U.S. by Guzmán López, whose lawyer denies those claims. Joaquín Guzmán López and his brother Ovidio are in plea negotiations with the U.S. government, their lawyers said this month in a Chicago courtroom.

Following the July arrests and Zambada’s allegations of kidnapping, horrific fighting erupted in Mexico between a cartel faction loyal to him and another tied to the “Chapitos,” Guzmán’s sons.

The Chapitos have used corkscrews, electrocution and hot chiles to torture their rivals while some of their victims were “fed dead or alive to tigers,” according to an indictment released by the U.S. Justice Department.

In recent months, bodies have appeared across Sinaloa, often left slung out on the streets or in cars with either sombreros on their heads or pizza slices or boxes pegged onto them with knives. The pizzas and sombreros have become informal symbols for the warring cartel factions, underscoring the brutality of their warfare.

The chain of events also strained relations between Mexico and the United States.

First, Mexico’s president at the time, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and current President Claudia Sheinbaum laid part of the blame for the bloodshed at Washington’s feet, saying the U.S. arrests uncorked trouble.

The outgoing U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Ken Salazar, responded that it was “incomprehensible” to suggest the cartel wars were Washington’s fault. He subsequently asserted that the Mexican government had stopped cooperating with Washington on fighting cartels and was sticking its head in the sand about violence and police corruption.

Mexico’s foreign ministry reacted by expressing “surprise” in a formal note to the U.S. embassy about the envoy’s statement.

www.cbsnews.com