Huntington disease, characterized by its profound impact on both cognitive and behavioral functions, is a complex and challenging neurodegenerative disorder. Karen E. Anderson, MD, a professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine, spoke with Medscape about the intricate genetic factors that influence its progression and symptoms.

What are the latest guidelines for the management of behavioral and cognitive symptoms of Huntington disease (HD)?

The behavioral working group of the Huntington Study Group and the European Huntington’s Disease Network published comprehensive guidelines for managing behavioral symptoms in HD in 2018.[1] These guidelines are based on expert consensus, as there are no large randomized clinical trials specifically addressing behavioral symptoms. While the behavioral guidelines have not been formally updated since then, there are certainly some recent reviews that discuss newer medications and offer additional approaches for managing symptoms.[2,3]

Cognitive symptoms in HD are a crucial aspect of the condition that we need to address. Although clinical options in this area are limited, the focus on cognitive symptoms in these trials represents a significant advancement. For example, Sage Therapeutics has the DIMENTION, SURVEYOR, and PURVIEW studies looking at their NMDA modulator as a possible treatment for HD cognitive impairment. Staying informed about these developments is important, as they could eventually lead to more effective treatments for cognitive symptoms and a better overall approach to managing HD.

We now have more resources for symptomatic care and end-of-life care, and can educate families and caregivers about the best ways to manage care at home or in professional settings. Social workers with HD expertise at centers can help with various social challenges.

Earlier this year, the CHDI Foundation’s annual therapeutic conference highlighted the role that increasing CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeats in somatic tissues (somatic expansion) play in HD disease progression.[4] Can you please share your thoughts on this hypothesis and its implications?

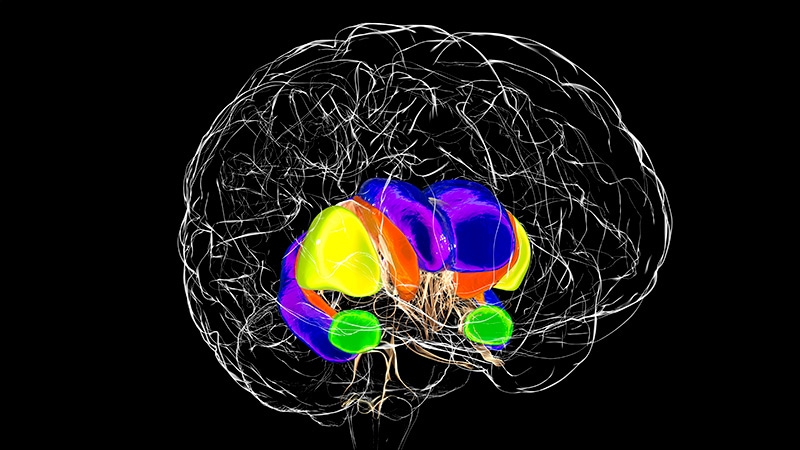

I think that it is certainly a component of the disease, although I don’t know that it explains the entirety of disease progression. In some tissues, these CAG repeats do seem to expand quite a bit, including in the liver and especially in the brain.[5] We see wasting and weight loss throughout the body, so even though we often think of it as a brain disease, we know that HD is truly a whole-body disease. It may not be the complete answer in terms of therapeutics, but addressing this question of how these repeats happen, what causes them, and whether there is a way to suppress or prevent the buildup of long CAG repeats in the peripheral tissues could be important therapeutically.

Are there any new insights related to the role of genetics in HD or mechanisms of DNA repair?

We think that some of the pathology is due to the body attempting to repair faulty DNA but perhaps doing too good a job by generating these long repeats, DNA mismatch repair. If there was a way to shut down these faulty repair mechanisms, we might be able to slow disease progression.[6] I still believe that lowering the huntingtin protein will be part of the solution. The huntingtin protein is integral to the disease, and we know it is abnormal in people with HD, who have both the wild-type normal protein and the mutant huntingtin protein. Therefore, addressing this aspect will remain a component of therapeutics, but it may require a combination of approaches.

With an average survival period of 15-18 years after the onset of symptoms, what are the most common mortality-related risk factors that clinicians should be aware of?

When someone is in later stages of HD, they often die or face complications like those seen in elderly people in nursing homes. We sometimes overlook these issues because patients with HD are often younger. However, someone in their 30s, 40s, or 50s can be in the final stages of the disease. In these late stages, patients are very prone to urinary tract infections and pneumonia. They are also at a high risk of falling, which can cause subdural hematomas — potentially fatal brain bleeds.

As the disease progresses, rapid weight loss is another major risk, like what is seen in patients with cancer or dementia. Choking and difficulty swallowing are signs that may indicate a person is nearing the end of life and which could lead to aspiration pneumonia.

Can you discuss the role of anti-inflammatory therapeutics in HD management? Are there any promising updates on the horizon?

Currently, we don’t have any approved anti-inflammatory therapies for HD, although some have been studied. We believe that some of the pathology in HD, as well as in other neurodegenerative diseases, is related to the brain’s reaction to the disease, leading to abnormal chronic inflammation. This inflammation can occur years before visible neurologic symptoms appear.[7]

While inflammation is normally a protective response, in conditions like HD, chronic inflammation can lead to neurotoxicity, damaging brain cells and accelerating neuronal death. We are investigating ways to suppress this abnormal immune reaction that occurs early in HD.